Nature’s Cure-Alls

In the late 1950s and 60s, it was not uncommon for a daily dose of foul-tasting, fishy smelling liquid to be forced upon sickly children by their grandparents and cited as the cure for everything from arthritis and baldness, to boils and piles. Cod liver oil consumption was at its peak, simultaneously torturing yet improving the health of children and their families all over the world. In the decades that followed various other natural remedies came in and out of the limelight. Apricot seed kernels, goji berries and coconut oil all enjoyed their glory days – with some developing a near cult following. However, as time passed and science accumulated (or failed to accumulate), it became clear that these natural remedies weren’t really the ‘cure all’ they were sometimes promoted to be. In recent years, another natural medicine has forged ahead as the latest trendy cure-all taking the population by storm; yet this one has the scientific backing to boot.

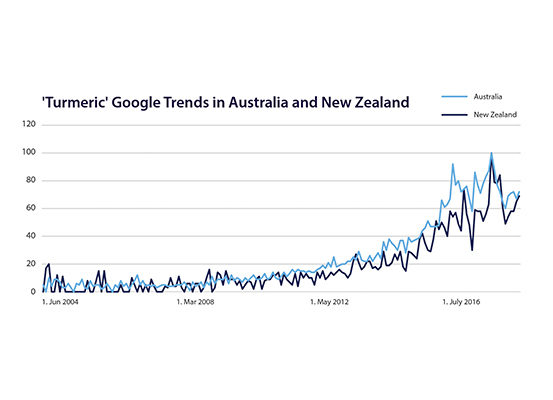

Figure 1a. Turmeric is Trending Amongst Consumers. Google Trends Showing the Public Interest in ‘Turmeric’ in Australia and New Zealand.

Figure 1b. Turmeric is Trending in Research. PubMed Citations Containing ‘Turmeric’ by Year.

A Condiment and a Cure

The cultural and medicinal history that surrounds turmeric is one that transcends time. Used for at least 6000 years in traditional medicine, food preparation and religious practice, it was long considered to be a sacred harbinger of prosperity amongst many Indian communities. Today, a cascade of promising studies have verified the value it brings. Developing a strong reputation as an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant early on, turmeric now boasts over 7500 scientific publications, which show it benefits a huge array of health conditions: arthritis1,2 cardiovascular disease,3 Alzheimer’s disease4 improved oral hygiene;5 it even has anti-ageing properties. You name the ailment, there is a good chance turmeric has been indicated to be of benefit – and that what you’ve heard is true. Unsurprisingly, all of these emerging health applications have roused a huge love affair with turmeric which has seen turmeric supplements prosper commercially, almost doubling sales within a year.6 However, like all great love affairs it is not without some challenges, and emotional baggage.

Curcumin – Just One Part of a Whole

First isolated in 1815, curcumin, the constituent that gives turmeric its yellow colour, takes much of the credit for the overall benefits of turmeric. This has led to the influx of several isolated curcumin supplements onto the natural medicines market. However, as the wise Greek philosopher Aristotle once proclaimed, the benefits of the whole herb is much greater than the sum of its parts, or more specifically, than one part alone. Certainly, curcumin is a gifted compound however, the whole turmeric root also provides resins and other volatile oils such as turmerones which offer additive anti-inflammatory,7 antimicrobial8 and anticancer9 effects. The first challenge when selecting the most appropriate turmeric supplement to engage in a relationship with, is to ensure you opt for the whole herb (i.e. the label reads Curcuma longa – Turmeric) to achieve the best outcomes; as using curcumin alone limits its therapeutic potential.

Turmeric’s Emotional Baggage

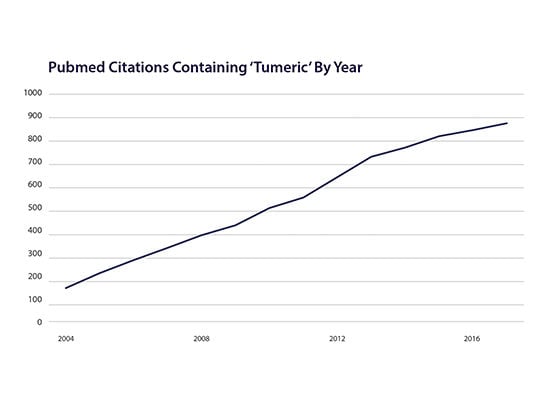

What many don’t realise is, regardless of whether you select the whole turmeric or curcumin alone, another major relationship conundrum remains: the compound curcumin (which comes with both) has notoriously poor bioavailability, meaning, it has low absorption and uptake into the body (aka the emotional baggage) (Figure 2).10 In fact, several animal studies have shown that as much as 90% of oral curcumin is excreted (from the other end). Drinking your daily turmeric latte and having the occasional Indian takeaway, therefore, could be giving you a false sense of security – that you’re obtaining all the potential health gains from this extraordinary herb, however you may not actually be absorbing sufficient levels. Turmeric supplements help overcome this relationship hurdle by providing concentrated extracts, which far exceed even the most impressive dietary intakes of curry. That said, absorption issues still need to be addressed, something that every manufacturer of Turmeric supplements is aware of.

Figure 2: Bioavailability Refers to How Well Something Can be Absorbed and Used by Your Body.

The Turmeric Arm’s Race

In response to the analyses proving poor turmeric absorption, a competitive buzz has been generated amongst supplement manufacturers who strive to meet the challenges of this talented yet temperamental therapy. Hi-tech, impressive-sounding bioavailability technologies such as nanoparticles, liposomes, micelles and phospholipid complexes – anything which can get it out of the intestines and into the blood as efficiently as possible – are constantly being evaluated and promoted to health professionals and consumers alike.11 Fortunately, the whole herb does enhance curcumin absorption thanks to the addition of the volatile oils. Many of the other options are heavily reliant on additives to perform, and as one tablet can only fit so many ingredients before it becomes a ‘horse-pill’, this often comes at the expense of the curcumin content itself. It is also very difficult to evaluate which technology is the leader in this turmeric arm’s race. Head-to-head studies directly comparing the different technologies are sparse, and they use different methodologies to assess absorption – so for the most part it can be like comparing apples with oranges. To throw another spanner in the works, the latest science on turmeric is showing that while bioavailability is likely important, it may not be the sole or even primary factor that determines its effectiveness. That’s because the time turmeric spends in the digestive tract contributes to its health benefits across all systems of the body – including the joints, heart and brain.

Health Begins in the Gut

Perhaps the single most recited quote amongst natural medicine circles is that from Hippocrates: “all disease begins in the gut.” Sharing this wisdom over 2000 years ago, we now have scientific confidence that truer words have never been spoken. The surface area of the inner lining of the digestive tract is thought to be roughly the size of a studio apartment12 – and even though it technically sits inside of our body, it acts as the primary interface with our outside environment. Not only is it a direct physical barrier protecting against entry from the constant assault of inflammatory toxins, dietary antigens, and microbes (like bacteria), it houses more nerves than the rest of our nervous system put together, and directs more immune decisions in one day than the entire immune system makes in a lifetime. In addition to this impressive resume, it is also home to a more than a 90% share of the human microbiome (the microbes that live on us and in us) – which in the last decade has proven to be intimately connected with all aspects of human health.

It comes as no surprise that weakening of the gut barrier, sometimes referred to as ‘leaky’ gut (meaning inflammatory compounds can leak into the blood stream), and disruption of the levels of the gut’s microbial inhabitants, has been linked to almost every known health disorder. This includes digestive conditions, autoimmune disease, allergies, metabolic dysfunction, and mental health imbalances such as depression.13,14 Interestingly, turmeric has been shown to benefit many of these conditions.

The New Age Antidepressant

To isolate just one example, Australia’s very own psychologist and researcher Dr Adrian Lopresti, has published several impressive studies, finding the specific extract BCM-95™ Turmeric, when taken alone and in combination with the herb saffron, improves symptoms of major depression.15 There are multiple mechanisms to explain how it helps, but of most significance is its ability to reduce inflammation and increase protective compounds within brain regions that have been implicated in depression16,17 Yet again, it is not just the curcumin, but tumerones found within the whole herb that contribute to its antidepressant activity.18 While we’ve concluded that many of these actions are reliant on turmeric’s systemic tissue distribution, our assumptions may have been slightly misguided.

Exciting new evidence over the past decade has identified strong links between depression, changes in the microbiome, and a leaky gut; with inflammation thought to play the key intermediary role. Hence, reducing gut inflammation is a key therapeutic target for depression, and many other conditions as well. Conceivably, it is this mechanism through which turmeric works.

The Gut Loves Curry

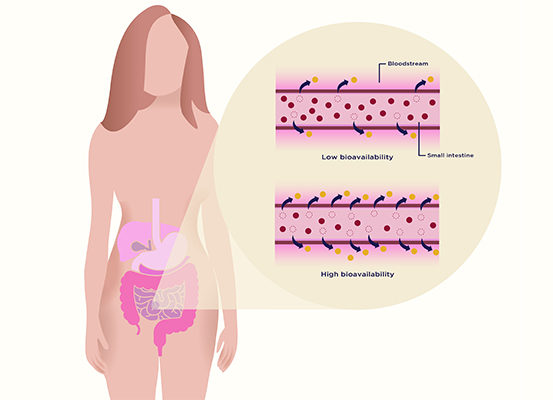

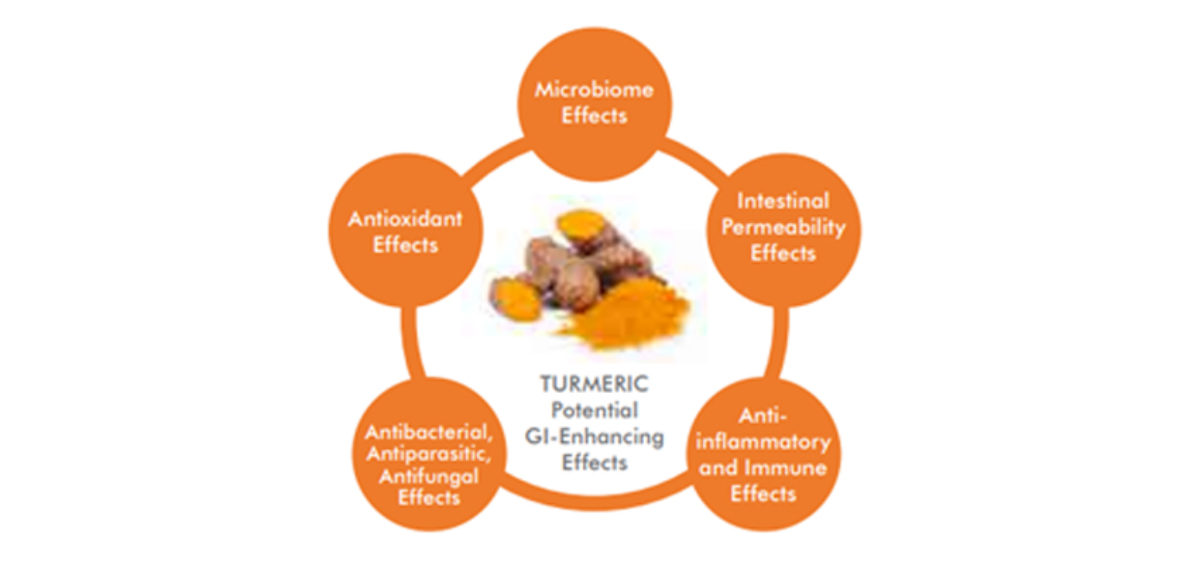

Although the research is still in its infancy, studies suggest that the system-wide medicinal benefits of turmeric are, at least in part, mediated through its ability to correct both gut barrier integrity and microbiome disturbances – local gastrointestinal actions that are not reliant on its absorption (Figure 3). Turmeric interventions have been shown to increase the activity of genes which promote gut barrier healing, and offset the negative effects of drugs known to significantly damage the gut barrier.19 In addition to improving barrier integrity, turmeric targets the gut microbes, increasing their richness and diversity – markers of a healthy gut microbiome.20 The net effect is reduced inflammation within the gastrointestinal tract and throughout the entire body – producing body-wide health benefits. These combined actions may not render the question around turmeric absorption obsolete, but highlight the limitations of focusing on bioavailability alone. Simply put, turmeric extracts may not necessarily need high bioavailability to be a highly effective health remedy. So, how do you choose the right turmeric for you? Opt for extracts that produce the most impressive results when trialed in humans for the condition that you are taking turmeric for. For example, BCM-95™ is a great option for depression, and has also produced impressive results for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. If you are not sure how to interpret clinical data yourself, speak to your naturopath or a Healthcare Practitioner who can. One thing we can predict with high probability, turmeric will continue to be trusted, loved and respected as a golden example of the benefits of natural therapies.

Figure 3: Potential Gastrointestinal-Enhancing Effects of Turmeric that May Contribute to its Systemic Health Effects.

References

1. Horayan A, Mukuchyan V, Mkrtchyan N, Minasyan N, Gasparvan S, Sargsyan A, et al. Efficacy and safety of curcumin and its combination with boswellic acid in osteoarthritis: a comparative randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;18(1)7. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-2062-z.

2. Chandran B, Goel A. A randomized pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of curcumin in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Phytotherapy Research. 2012 26(11): 1719-25.

3. Hewlings S, Kelman D. Curcumin: a review of it’s effect on human health. Foods. 2017 Oct 22;6(10). doi: 10.3390/foods6100092.

4. Mirmosayyeb O, Tanhaei A, Sohrabi HR, Martins RN, Tanhaei M, Najafi MA, et al. Possible Role of Common Spices as a Preventive and Therapeutic Agent for Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Prev Med. 2017 Feb 7;8:5. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.

5. Pulikkotil SJ, Nath S. Effects of curcumin on crevicular levels of IL-1β and CCL28 in experimental gingivitis. Aust Dent J. 2015 Sep;60(3):317-27

6. Natural Products Insider. 2016;6(14).

7. Del Prete D, Millan E, Pollastro F, Chianese G, Luciano P, Collado JA, et al. Turmeric Sesquiterpenoids: Expeditious Resolution, Comparative Bioactivity, and a New Bicyclic Turmeronoid. J Nat Prod. 2016 Feb 26;79(2):267-73. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00637

8. Prasad S, Gupta SC, Tyagi AK, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin, a component of golden spice: from bedside to bench and back. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32:1053–1064.

9. Tyagi AK, Prasad S, Yuan W, Li S, Aggarwal BB. Identification of a novel compound (β-sesquiphellandrene) from turmeric (Curcuma longa) with anticancer potential: comparison with curcumin. Invest New Drugs. 2015 Dec;33(6):1175-86.

10. Burgos-Morón E, Calderón-Montaño JM, Salvador J, Robles A, López-Lázaro M. The dark side of curcumin. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1771-5

11. Prasad S, Gupta SC, Tyagi AK, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin, a component of golden spice: From bedside to bench and back. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32:1053-64.

12. Helander HF, Fändriks L. Surface area of the digestive tract – revisited. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014 Jun;49(6):681-9. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.898326.

13. Lloyd-Price J, Abu-Ali G, Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 2016;8:51.

14. Amalraj A, Pius A, Gopi S, Gopi S. Biological activities of curcuminoids, other biomolecules from turmeric and their derivatives – A review. J Tradit Complement Med. 2017 Apr;7(2):205–233.

15. Lopresti AL, Maes M, Maker GL, Hood SD, Drummond PD. Curcumin for the treatment of major depression: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2014;167:368-75.

16. Pereira Dias G, Cavegn N, Nix A, do Nascimento Bevilaqua M, Stangl D, Zainuddon M, et al. The Role of Dietary Polyphenols on Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis: Molecular Mechanisms and Behavioural Effects on Depression and Anxiety. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012;2012:541971.

17. Xu Y, Ku B, Tie L, Yao H, Jiang W, Ma X, et al. Curcumin reverses the effects of chronic stress on behavior, the HPA axis, BDNF expression and phosphorylation of CREB. Brain Res. 2006 Nov 29;1122(1):56-64. Epub 2006 Oct 3.

18. Lopresti A. The Problem of Curcumin and Its Bioavailability: Could Its Gastrointestinal Influence Contribute to Its Overall Health-Enhancing Effects? Advances in Nutrition. 2018;9(1):41-50.

19. Lopresti A. The Problem of Curcumin and Its Bioavailability: Could Its Gastrointestinal Influence Contribute to Its Overall Health-Enhancing Effects? Advances in Nutrition. 2018;9(1):41-50.

20. Lopresti A. The Problem of Curcumin and Its Bioavailability: Could Its Gastrointestinal Influence Contribute to Its Overall Health-Enhancing Effects? Advances in Nutrition. 2018;9(1):41-50.

21. Adapted from: Lopresti A. The Problem of Curcumin and Its Bioavailability: Could Its Gastrointestinal Influence Contribute to Its Overall Health-Enhancing Effects? Advances in Nutrition. 2018;9(1):41-50

Is What You Heard About Turmeric True?

Is What You Heard About Turmeric True?